Let’s keep on exploring the data challenge that renewable energy producers face. We previously identified two factors for that:

- The ongoing Energy Transition (as seen in our previous post)

- The development of Market based revenues for Renewable Energy Producers

Read all previous posts here!

Let’s first rewind a bit to understand where Market based revenues come from.

Episode 1: From feed-in tariffs to Market based revenues

As soon as 1990 in Germany*, renewable energy production used to be supported by feed-in tariffs. This means that every asset could benefit from a predefined price for each MWh produced over a long period (for up to 20 years). Along with priority dispatch obligation for renewables given to grid operators, this predefined price was rather high in order to help develop the renewable industry. After the good results of this feed-in tariff policy, other European countries followed the same approach and feed-in tariffs became widely adopted as a strong support for renewables.

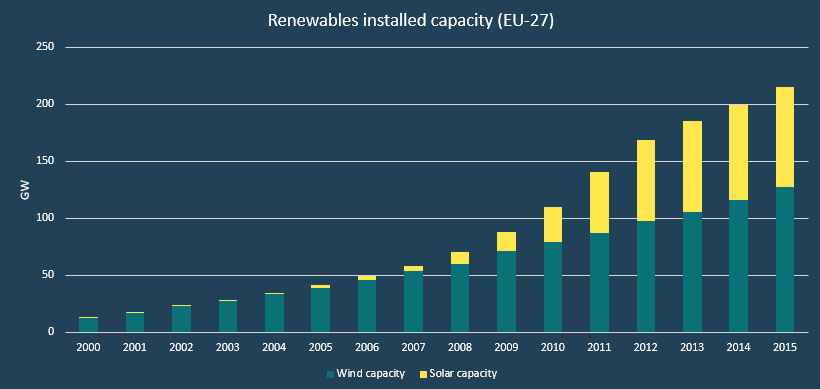

During those years production was paid a feed-in tariff on an “as produced” basis meaning that there was strictly no incentive to align production and consumption for renewable producers. The only incentive was to produce whenever possible. As a consequence, wind and solar grew well. And to be honest, well beyond expectations. No one really thought that feed-in tariffs would have such an effect. Which inevitably led to an emerging issue. One must not forget that at the same time, since the early 2000s, EU decided to develop the power market. And during this period, the EU power market developed with more and more (conventional) production and consumption being sold and sourced on market, mainly via derivatives (Futures) and physical (Spot) markets.

So on the one hand, thanks to feed-in tariffs, renewable production grew and was incentivized to produce “as much as possible” and on the other hand EU power markets were expanding with “price signals” principles for both conventional producers and consumers. This situation inevitably led to a critical contradiction as renewable producers were not obliged to contribute to grid stability and as there was a clear rising risk to see negative prices when production is higher than consumption. This would make consumers happy, but would cause problems to more conventional production assets.

Back in 2012, in order to mitigate this risk, the German government introduced an alternative scheme to the feed-in tariffs: the Market Premium scheme. With this new scheme, voluntary renewable plants operators became in charge of selling their production on the market, thus taking into account price signals. But in order to still support the development of renewables, a variable Market Premium fee was paid to the renewable producers on top of their market remuneration (plus a fixed management premium fee to cover market access, balancing and other operational fees). This is what we could also call a Contract for Difference (“CfD”) where the buyer pays the seller the difference between a reference price (here the feed-in tariff) and the realized price (here the technology specific average market price). As it proved as a good tool to mitigate the negative prices risk**, many countries followed German initiative on Market Premium scheme.

Another problem was that feed-in tariffs did not make it possible to control the number of new renewable assets and projects: feed-in tariffs and market premium schemes were accessible to any renewable producer. There was a clear risk for an overheated market. That is why, under the impulsion of EU, some auctioning principles were introduced in order to select new renewable projects on the basis of an auctioning process: producers bid on the reference price of the Contract for Difference (CfD) and sell their production on the market.

That’s how market based revenues for renewable production were introduced. And it seems that today, auctioning process with Contracts for Difference (CfDs) are widespread. Renewable energy now has a clear incentive to produce only when market needs it. However, in the end, we have to admit that this did not prevent the explosion of negative prices. In a way it just delayed it. This will be an interesting topic for a future post!

…Stay connected for Market Based Revenues episode 2!

Read all previous posts here!

* You can read this very detailed and interesting study that recaps how feed-in tariffs were introduced in Germany

** Read some interesting study that evaluated that such a market premium scheme impact on the number of hours with negative prices